The aircraft modeling story of 90-year old modeler, Weston Jenkins continues here on FlyBoyz with Part 2 of his tale. Earlier this year, I asked my friend Weston to write about anything that he thought would be relevant relating to his 8+ decades as a modeler and aviator which began shortly after the epic trans-Atlantic flight of Charles Lindbergh.

Now in his own words, here is Weston Jenkins and Part 2 of his ‘Aviation Magnus Opus‘.

One Old Boy’s Airplane Story – Part 2

Weston H. Jenkins – October 2014

It’s a funny thing how your mind works when you’re 90…I can brush my teeth and immediately forget whether I have finished or am just thinking of it. The solution to that dilemma is to feel the toothbrush to see if it’s wet.

But there are certainly minute recollections related to model airplanes. Maybe that is because when one builds them, trims them, and flies them there is developed an intimate relationship between each one and one’s self. Think about that, (but not too much).

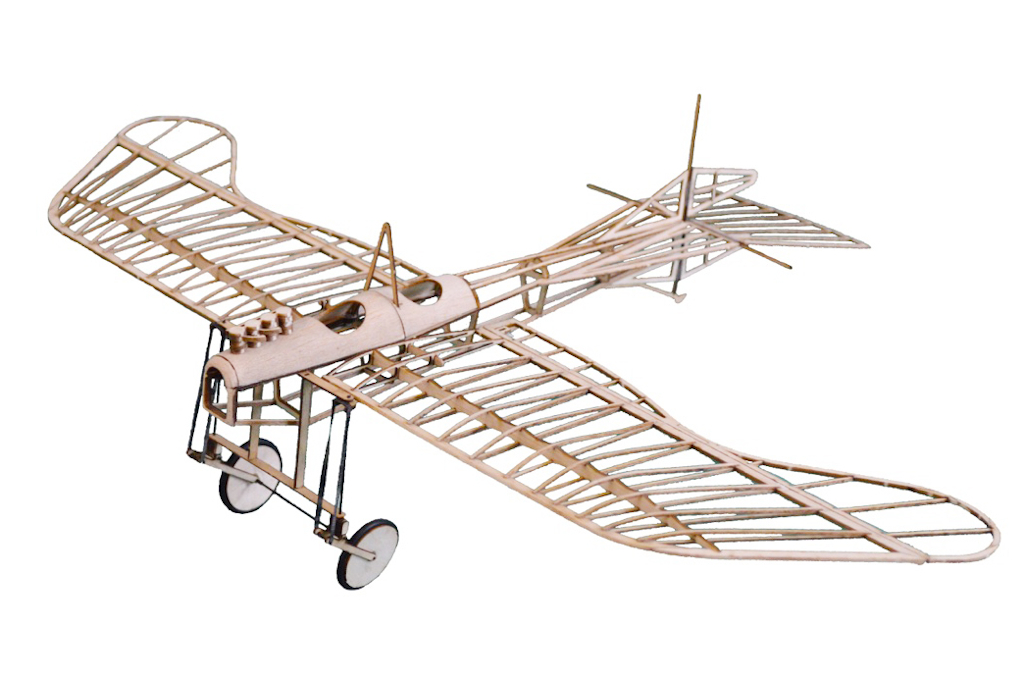

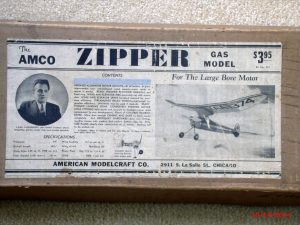

World War II was underway in 1941 at high school graduation time. I rewarded myself with a Carl Goldberg designed Zipper kit produced by Comet and later sold under the name American Modelcraft Company with Carl’s picture on the box. With, I think, only a 54-inch wingspan and my trusty Brown D in it, it seemed like a holy terror. Everyone was flying them and, it appears, everyone in free flight still is. Oh, not actually Zippers, of course, but there have been few free flight gas models designed since which are not, with their pylon-mounted mounted wings, clearly the descendants of the Goldberg layouts, Valkyrie and Zipper. 75 years. Some progress, that. Curiously, this ran completely counter to the theory, of which engineer-author-editor Charles Hampson Grant had convinced me, that a low center of lateral area would be a key to stable flight. No, I did not have the pleasure of knowing Mr. Grant, but, although with limited understanding, I read his quite technical articles in Model Airplane News religiously. Try to find any model airplane magazine articles of equal quality these days.

With, I think, only a 54-inch wingspan and my trusty Brown D in it, it seemed like a holy terror. Everyone was flying them and, it appears, everyone in free flight still is. Oh, not actually Zippers, of course, but there have been few free flight gas models designed since which are not, with their pylon-mounted mounted wings, clearly the descendants of the Goldberg layouts, Valkyrie and Zipper. 75 years. Some progress, that. Curiously, this ran completely counter to the theory, of which engineer-author-editor Charles Hampson Grant had convinced me, that a low center of lateral area would be a key to stable flight. No, I did not have the pleasure of knowing Mr. Grant, but, although with limited understanding, I read his quite technical articles in Model Airplane News religiously. Try to find any model airplane magazine articles of equal quality these days.

Re-covered and re-engined with a Comet 35 and then with a Torpedo, my Zipper was still around in about 1995, when it was sold at a club auction. It had been tried with radio control of a rudder tab with very negative, but repairable, results.

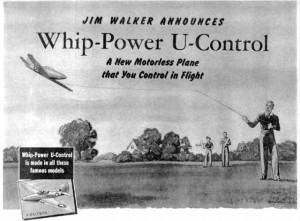

What with the war, it looked as though it would be all over for the models for the duration. However, the Army gave me 3 months of instruction at a small teachers’ college as preparation for entering the aviation cadet program.  There was an athletic field/parade ground suitable for control line flying. It was possible to assemble a sheet balsa whip-powered P-39 profile model and actually engage in dizzy flight. The power came from a stick with fairleads attached to it, like a fish pole. Control lines ran from the handle through these guides out to the airplane. It was launched by an assistant who threw it, and the pilot kept it going by leading it with the “fish pole” in one hand while manipulating the control handle with the other. Better than nothing.

There was an athletic field/parade ground suitable for control line flying. It was possible to assemble a sheet balsa whip-powered P-39 profile model and actually engage in dizzy flight. The power came from a stick with fairleads attached to it, like a fish pole. Control lines ran from the handle through these guides out to the airplane. It was launched by an assistant who threw it, and the pilot kept it going by leading it with the “fish pole” in one hand while manipulating the control handle with the other. Better than nothing.

In the training program we moved from base-to-base, all over the country, Florida, Texas, California, Idaho, and a number of points scattered between. At almost every stop, I was able to set up to somehow build a model airplane. Some were kit-built…. balsa was in short supply so some parts were of cardboard or spruce. The best setup was in the officers’ quarters at Mountain Home, Idaho. I actually had a two-bed room to myself in one of those tarpaper barracks. The beds were end-to end, so the door taken from a wooden locker, laid across between the head and foot of the unused bed, made a dandy workbench, at just the right height. First there was quite a detailed “solid” model of a B-24. (The situation was favorable for sketching details because that is what we were flying at the time.) It came out well, but a wing was broken off when it was shipped home by Railway Express.

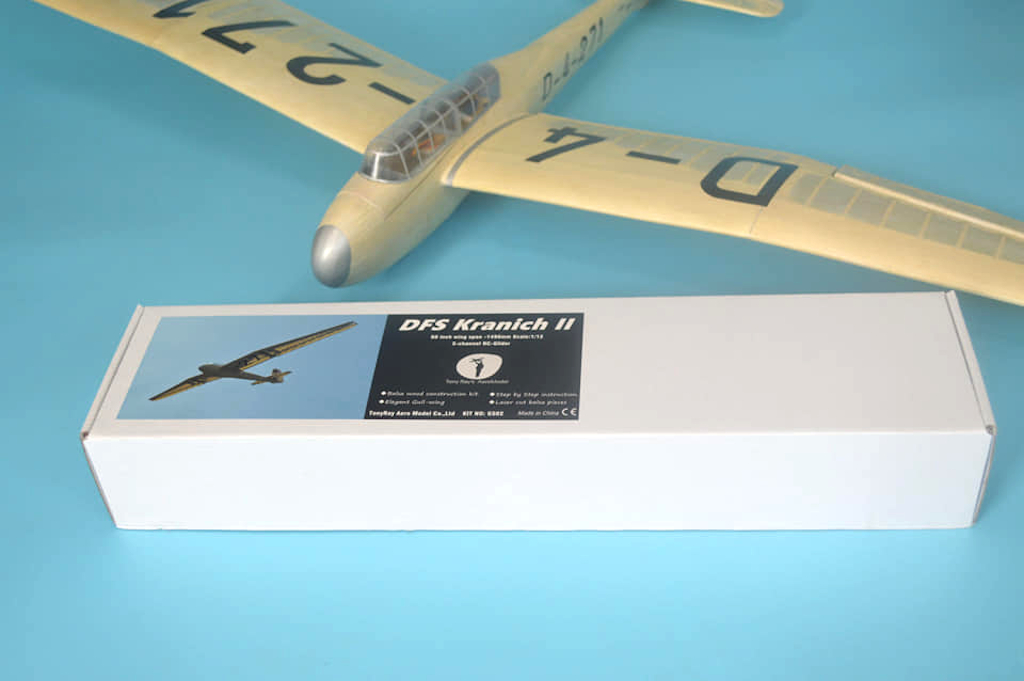

Then, on the same bench, there arose a 10-foot Cleveland sailplane (“Condor”, I believe, but perhaps “Albatross”). There is no remembering how it was done, but I shipped that home and it came through without damage. There was no winch, and running with it to tow it up was a little much, but about thirty years later it was fitted with RC rudder control and a top-mounted electric motor with very satisfying results. Its usefulness ended when I strained it through a tree. The mind-picture of that event distresses me to this day.

Then, on the same bench, there arose a 10-foot Cleveland sailplane (“Condor”, I believe, but perhaps “Albatross”). There is no remembering how it was done, but I shipped that home and it came through without damage. There was no winch, and running with it to tow it up was a little much, but about thirty years later it was fitted with RC rudder control and a top-mounted electric motor with very satisfying results. Its usefulness ended when I strained it through a tree. The mind-picture of that event distresses me to this day.

Scratch building in those days was sometimes pretty scratchy. Materials and parts were hard to come by. At one point, desperation led to making a paper glider out of notebook paper, rolled-tube fuselage, fairly thick airfoil, thread towline. Once it actually stayed up for about a minute, a real thrill. Again, there was a U-control airplane with an Atwood P-30 engine. It was built by soldering together pieces of coat hanger wire and covering with newspaper. It was painted with enamel from the ten-cent store. It never flew, but not for the reason that would first come to the reader’s mind. The fact was that every time it was ready to lift off the engine quit. Time ran out, we had to leave that base, and it wasn’t worth sending home. I saved the engine, the spark coil, and the condenser, of course.

As things progressed, I found myself bound by troopship for the South Pacific. Hopeful for a chance to build something, I included a nice Atwood .60 in my baggage. The baggage was shipped separately from me; when it arrived in the Philippines, the Atwood had disappeared, so I wrote home for a few HO freight car kits. War is Hell.

As things progressed, I found myself bound by troopship for the South Pacific. Hopeful for a chance to build something, I included a nice Atwood .60 in my baggage. The baggage was shipped separately from me; when it arrived in the Philippines, the Atwood had disappeared, so I wrote home for a few HO freight car kits. War is Hell.

<<End Part 2>>