Several months ago, I was introduced to Claudio Elicer Avalos via some photos of a PA-28 model that he posted in a Free Flight Group on Facebook. Claudio was building the PA-28 and was documenting his build via a series of photos. I was impressed with the level of craftsmanship that was evident in the photos and struck up a conversation with him related to his build. One thing led to another and I finally asked Claudio if he would be willing to share his building and flying experiences with others via a FlyBoyz Guest Post. Claudio graciously agreed to do so.

One thing that excited me about this post was the thought that it would represent a great opportunity to learn about modeling and flying in another country, in this case in Chile, South America. Claudio lives in Santiago, Chile and I was curious to learn about differences, if any, to how modeling and flying is approached in that part of the world. One difference is language. In Chile, Spanish is the primary language. Fortunately for me, Claudio has a very good grasp of the English languish so communication between the two of us has not been an issue. When it came to his FlyBoyz post, Claudio elected to write it in his native Spanish and then the two of us collaborated on the English translation of it. This Spanish to English translation gave me the opportunity to try out a FlyBoyz first…a bilingual article!

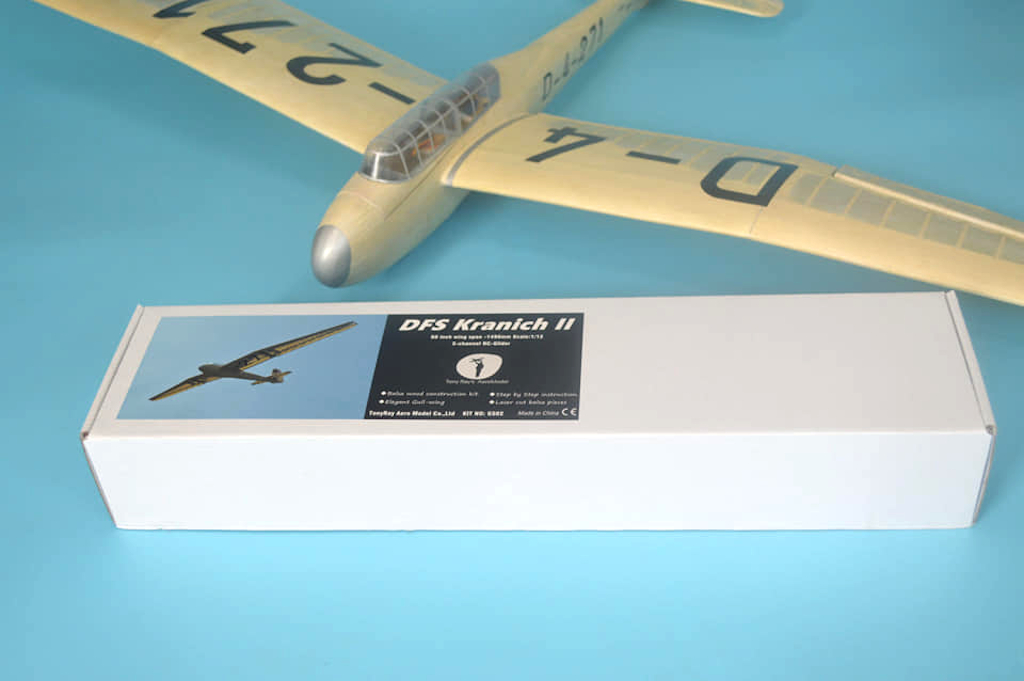

Claudio’s post is actually being broken into two posts, this first one is focusing on his full scale aviation experience and the lessons he applied from it to his model flying. The second post will feature his awesome build of his PA-28 model. Both posts will be presented first in our English translation version and then the post will be repeated in Spanish exactly as Claudio wrote it. I hope everyone enjoys these posts and appreciates both Claudio’s efforts at preparing them as well as the level of craftsmanship he displays in building his PA-28. Please feel free to leave comments to Claudio.

Here now is Part 1 ‘From Pilot to Model Airplane Enthusiast‘ of Claudio’s report from South America!

From Pilot to Model Airplane Enthusiast

Claudio Elicer Avalos – November 2014

Introduction

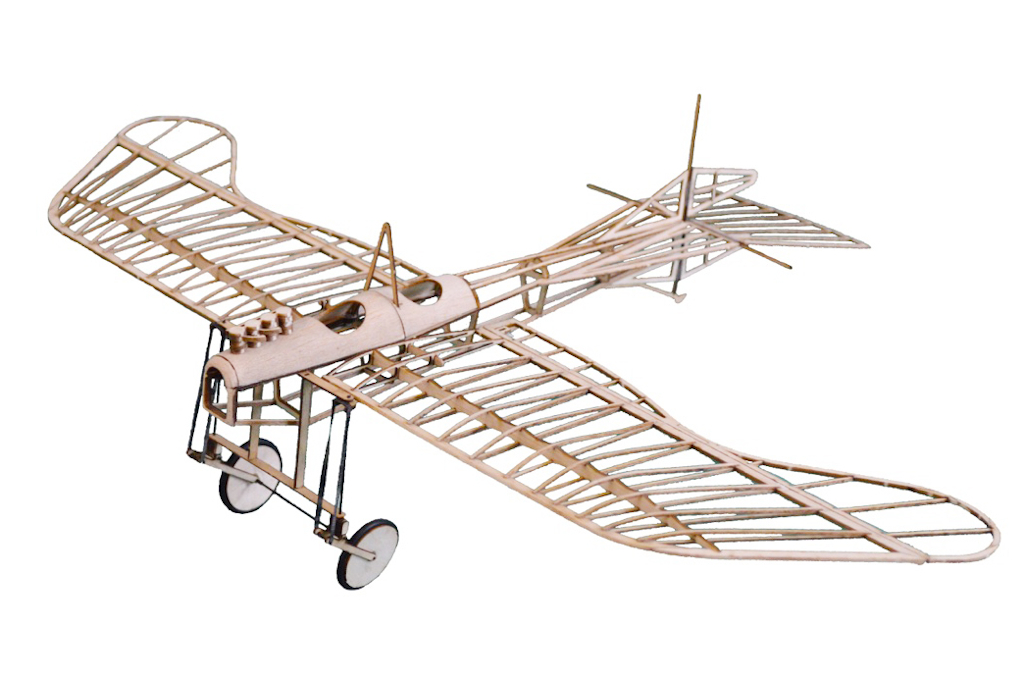

If you ask me how long I have liked airplanes, I’d say from 4 or 5 years old, when I received the gift of a kit to build, a model with a rubber engine. I just remember it was a profile type fuselage with wings and paper structure. Perhaps this simple event marked my beginning. Then I decided to be a pilot, because it was obvious to me my passion for flying. As an adult, I got my civilian pilot’s license, and I thought this would be an activity that would accompany me throughout my life. But after 250 hours, I realized that I my time as a pilot had passed, and there were other flights that I was really looking for the rest of my life.

I began my life as a civilian pilot in 1995, and flew as much as my wallet allowed me to. In Chile there are several air clubs where you can learn to fly and use the planes belonging to the clubs. Here there are very few who have the privilege of flying their own aircraft, although I think if you want to fly a couple of weekends a month, it is a very good alternative.

My training was hard, much harder than I imagined. I even went so far as to think that I would not be able to get my license after 40 hours, since I received few congratulations from my instructor, but eventually I realized that he just wanted to be sure that I was prepared, and for that I had to demonstrate to him that I would be capable of solving complicated situations for myself … and I finally succeeded.

In my career, I learned that a pilot who has not had any real emergency is not a real pilot … And I had three emergencies that put me to the test: the first was due to a short circuit that produced a lot of smoke in the cockpit, by a capacitor that burned. Immediately, I shut off the Master and everything calmed down, but the radio and all electrical instruments stopped working. The second time, I landed on an uncontrolled track close to the sea, with a headwind so strong that the plane began to lose altitude without much progress. I had to apply full power of the engine to get to the track … I had never done that before. The third and hardest was also on an uncontrolled track, where I landed with the wind, very strong, and the brakes failed to stop the plane. I was forced to abort the landing by applying full power, when we had already exceeded half of the track … the track ended and the speed of the plane did not reach the green arc (Green Arc) … again I did something I had never done before: I rotated the plane without the speed necessary to do so, the stall alarm sounded stronger than my heart. It was horrible. I remember that the plane, a Cessna 172, rose enough to exceed the wire fence and then began to fall, so I lowered the nose for the aircraft to increase its speed, lucky for me because the ground sloped down toward the lake, which allowed me to not crash to the ground.

Since that time as a pilot, I became obsessed with building free flight models, but models I had personally piloted, such as Cessna and Piper classics that were my favorites and I knew very well. From this I can say that the differences in the way you fly both types of aircraft is observed in the models; the Cessna, a plane very stable but slower to react, and the Piper, a plane less stable but more maneuverable, both very good.

At present I live in Santiago, the capital of Chile, a country worth knowing, with a long and narrow geography, which possesses all the climates of the world and an infinite variety of sceneries, with beaches and mountains an hour away. I had the privilege of knowing my country from the air.

Some Tips That Aviation Taught Me

The pilot activity allowed me to understand some aspects that later applied to my free flight models, which I had been building since before becoming a pilot. I want to highlight 5 points to take into account to be successful with free flight models:

-

A fundamental aspect is the relationship between the weight of the model, the engine power and the lift provided by the wing. The real aircraft has a maximum takeoff weight which must never be exceeded. In our case, the weight that our model acquires to scale is, in my opinion, the most important factor for the model to achieve a stable and “scale” flight. It is a mistake to think that increasing the power supply will overcome model weight. This means at least sacrificing the flight “to scale”, a usual case in radio-controlled models with combustion engines or electric models, which are generally enhanced. In rubber powered free flight scale models, the power to be used should be the minimum necessary to achieve a graceful flight, and it is absolutely necessary for the model to be as light as possible.

-

Single-engine propeller aircraft have a very accentuated P factor (propeller factor), which is the tendency of the aircraft to rotate due to the torque produced by the engine which is transferred to the propeller, which rotates in the opposite direction (or Newton’s Third Law). Consequence: the plane lowers a wing, while the other one rises, just because of the P factor.

-

Planes change direction because they lower a wing while other one rises. The rudder collaborates to do a more “coordinated” turn or with less horizontal forces that appear when a plane changes direction, but it is not its main function to make to change direction to a plane. The P factor has a much more pronounced effect on a free flight model airplane than in a real airplane since in general are used propellers of greater proportion than in a real airplane, the model tends to veer sharply in the opposite direction to the torque produced by the engine, in this case, to the left. This is a very important factor to take into account for a free flight model. In real aircraft, this trend or imbalance is corrected by adjusting the vertical and horizontal angle of the propeller shaft, which we also must know how to do. Consequence: P factor makes the plane turn left, without adjusting any control plane, therefore, to turn right means sacrificing a bit of power just to counteract the P factor, resulting in lower model flying capacity.

-

Real planes fly straight and level with the elevator in neutral or nearly neutral. The elevator angle is changed by the pilot only to change the attitude of the aircraft during takeoff and landing approach, but for straight and level flight under normal conditions, the elevator position must be neutral; otherwise it means that the position of the center of gravity is incorrect. Consequence: the flight attitude of the model has to be adjusted by varying the angle of the propeller shaft, the center of gravity, or both, never the elevator.

-

When an aircraft flys straight and level, an increase of engine power will generate a rise of the aircraft or change in attitude, while a decrease in power, results in down, without varying the angle of the lift … obvious (or not that obvious?). Consequence: our model must climb, fly and descend just by the effect of the discharge of the rubber motor.

For a free flight rubber model, unless radio control systems or clockworks are used, control planes must be set in position before takeoff. If we add the effect of the variable power delivered by the engine rubber, with all its power at the beginning of the discharge, and gradually decreasing over the next few seconds, achieving a stable flight, both mounted, level flight and descent in gliding, it becomes an almost impossible task.

De Piloto a Aeromodelista

Claudio Elicer Avalos – Noviembre 2014

Presentación

Si me preguntaran desde cuándo me gustan los aviones, diría que desde los 4 o 5 años de edad, cuando recibí de regalo un kit para armar de un modelo con motor a goma. Sólo recuerdo que era un modelo de fuselaje tipo perfil con alas de estructura y papel. Tal vez ese simple acontecimiento marcó mi comienzo. Después decidí que sería piloto, porque para mí era obvia mi pasión por el vuelo. Siendo un adulto, obtuve mi licencia de piloto civil, y pensé que esa sería una actividad que me acompañaría durante toda mi vida. Pero al cabo de 250 horas de vuelo, me di cuenta que mi época de piloto había pasado, y que eran otros los vuelos que yo realmente buscaba para el resto de mi vida.

Comencé mi vida como piloto civil en 1995, y volé tanto como mi billetera me lo permitió. En Chile existen varios clubes aéreos donde se puede aprender a volar y utilizar los aviones pertenecientes a los clubes. Acá son muy pocos los que tienen el privilegio de volar aviones propios, aunque pienso que si se quiere volar un par de fines de semana al mes, es una muy buena alternativa.

Mi entrenamiento fue duro, mucho más duro de lo que me imaginaba. Incluso llegué a pensar que yo no iba a ser capaz de obtener mi licencia al cabo de 40 horas, ya que recibía pocas felicitaciones de parte de mi instructor, pero al final me di cuenta que él sólo quería estar seguro de que yo estaba preparado, y para eso debía demostrarle que sería capaz de resolver situaciones complicadas por mí mismo…y finalmente lo logré.

En mi trayectoria aprendí que un piloto que no haya tenido alguna emergencia real no es un piloto de verdad…y yo tuve tres emergencias que me pusieron a prueba: la primera fue debido a un corto circuito que produjo gran cantidad de humo en la cabina, por un condensador que se quemó. Inmediatamente puse en Off el Master y todo se calmó, pero dejó de funcionar la radio y todos los instrumentos eléctricos. La segunda vez aterricé en una pista no controlada cercana al mar, con un viento en contra tan fuerte que el avión comenzó a perder altura sin casi avanzar. Tuve que aplicar toda la potencia del motor para poder llegar a la pista…nunca había hecho eso antes. La tercera y más dura fue también en una pista no controlada, en la cual aterricé con el viento, muy fuerte, y los frenos no pudieron detener el avión. Me vi forzado a abortar el aterrizaje aplicando toda la potencia, cuando ya había sobrepasado la mitad de la pista…la pista se acabó y la velocidad el avión no llegó al arco verde (Green arc)…nuevamente hice algo que nunca había hecho antes: roté el avión sin la velocidad necesaria para hacerlo, la alarma de stall sonaba más fuerte que mi corazón, fue horrible. Recuerdo que el avión, un Cessna 172, se elevó lo necesario para sobrepasar el cerco de alambres y luego comenzó a caer, por lo cual bajé la nariz para que la aeronave aumentara su velocidad, con mucha suerte para mí porque el terreno bajaba en pendiente hacia el lago, lo que me permitió no estrellarme contra el suelo.

Desde aquella época de piloto me obsesioné por construir modelos de vuelo libre, pero modelos que yo personalmente había piloteado, como los clásicos Cessna y Piper que fueron mis favoritos y que conocía muy bien. De esto puedo decir que las diferencias en la manera de volar de ambos tipos de aviones se observa en los modelos; el Cessna, un avión muy estable pero más lento para reaccionar, y el Piper, un avión menos estable pero más maniobrable, ambos muy buenos.

Actualmente vivo en Santiago, la capital de Chile, un país digno de conocer, con una geografía larga y angosta, que posee todos los climas del mundo y una variedad de paisajes infinita, con playa y montaña a una hora de distancia. Tuve el privilegio de conocer mi país desde el aire.

Algunos Tips Que La Aviación Me Enseñó

La actividad de piloto me permitió comprender algunos aspectos que más tarde apliqué a mis modelos de vuelo libre, que venía construyendo desde antes de ser piloto. Quiero destacar 5 puntos que hay que tener muy en cuenta para tener éxito con los modelos de vuelo libre:

-

Un aspecto fundamental es la relación que existe entre el peso del modelo, la potencia del motor y la sustentación que provee el ala. Los aviones reales tienen un peso máximo de despegue que no debe ser sobrepasado nunca. En nuestro caso, el peso que adquiera nuestro modelo a escala es, a mi juicio, el factor más importante para que el modelo logre un vuelo estable y “a escala”. Es un error pensar en que aumentando la potencia supliremos un sobre peso del modelo. Esto significa al menos sacrificar el vuelo “a escala”, caso habitual en modelos radiocontrolados con motor a explosión o eléctricos, modelos que están generalmente sobrepotenciados. En modelos a escala de vuelo libre con motor de goma, la potencia a utilizar debe ser la mínima necesaria para lograr un vuelo grácil, y para eso es absolutamente necesario que el modelo sea lo más liviano posible.

-

Los aviones monomotores a hélice tienen muy acentuado el factor P (factor Propela), que es la tendencia a rotar que tienen las aeronaves debido al torque que produce el motor y que es transferido a la hélice, la cual gira en sentido contrario (o Tercera Ley de Newton). Consecuencia: el avión baja un ala, mientras que la otra sube, sólo por el factor P.

-

Los aviones viran porque bajan un ala mientras que la otra sube. El timón colabora para hacer un viraje más “coordinado” o con menos fuerzas horizontales que aparecen cuando un móvil cambia de dirección, pero no es su función principal hacer virar a un avión. Dado que el factor P tiene un efecto mucho más acentuado en un aeromodelo de vuelo libre que en un avión real, ya que en general se usan hélices de mayor proporción que en un avión real, el modelo tiende fuertemente a virar en sentido contrario al torque que produce el motor, en nuestro caso, a la izquierda. Ese es un factor muy importante a tomar en cuenta para un modelo de vuelo libre. En aviones reales, esta tendencia o desbalance es corregido ajustando el ángulo vertical y horizontal del eje de la hélice, cosa que nosotros también debemos saber hacer. Consecuencia: el factor P hace que el avión gire a la izquierda, sin necesidad de ajustar ningún plano de control, por lo tanto, hacerlo virar a la derecha significa sacrificar un poco de potencia sólo para contrarrestar el factor P, lo que resulta en menor capacidad de montada del modelo.

-

Los aviones reales vuelan de forma recta y nivelada con el elevador en posición neutra o casi neutra. El ángulo del elevador es modificado por el piloto sólo para cambiar la actitud del avión durante despegues y aproximaciones, pero para un vuelo recto y nivelado bajo condiciones normales, la posición del elevador debe ser neutra; lo contrario significa que la posición del centro de gravedad es incorrecta. Consecuencia: la actitud de vuelo del modelo la tenemos que ajustar variando el ángulo del eje de la hélice, el centro de gravedad o ambos, nunca con el elevador.

-

Mientras un avión vuela recto y nivelado, un incremento de la potencia del motor generará un ascenso de la aeronave o cambio de actitud, mientras que una disminución de la potencia, un descenso, sin necesidad de variar el ángulo del elevador…algo obvio (o no tan obvio?). Consecuencia: nuestro modelo deberá ascender, volar y descender sólo por el efecto de la descarga del motor a goma.

En el caso de un modelo de vuelo libre a goma, a menos que se usen sistemas de radio control o mecanismos de relojería, los planos de control se deben fijar en posición antes del despegue. Si a eso le sumamos el efecto de la potencia variable que entrega el motor a goma, con toda su potencia al inicio de la descarga, y disminuyendo paulatinamente durante los segundos siguientes, lograr un vuelo estable, tanto en montada, vuelo nivelado y descenso en planeo, se transforma en una tarea casi imposible.