Weston Jenkins is an American model aviation treasure. Weston has been interested in and involved with aviation since Charles Lindbergh first flew across the Atlantic. Literally! For you see, Weston is a young 90 years old and still going strong!

I first ‘met’ Weston last spring (2013) when I purchased a kit from him that he had for sale on eBay. The kit was a vintage 1958 Berkeley Curtiss A-12 Shrike control line plane. When I received the kit, it was in near mint condition despite being 55 years old, so I wrote Weston and asked if he was the original owner of the kit (he was) and if he was able to tell me something about the history of that particular kit. The reply that I received wherein Weston proceeded to describe the ‘provenance’ of the kit was written in a style and to a detail that totally captured me. Thus began a ‘friendship’ that has resulted in me finally convincing Weston to share some of his model aviation experiences with the rest of my FlyBoyz readers.

Since purchasing that first kit, I have purchased no less than 4 more kits from Weston (Hawker Hart, Douglas Y10-43, Ryan ST, Inland Sport) all classics from the ‘Golden Age of Aviation‘ which Weston had the privilege of actually living through in real life. As great as the kits are that he sells on eBay, the descriptions that he includes are every bit as captivating as the kits themselves. A bit history lesson, and bit aviation poetry, his eBay descriptions are not to be missed! Thru Weston and his beautiful kits, I too have become a big fan of the planes of that wonderful bygone era and I look forward to building Weston’s kits with the same care and pride that he would have shown them.

I asked Weston to write about anything that he thought would be relevant relating to his 80+ years as a modeler and aviator. What follows will be presented as a multi-part FlyBoyz post.

Now in his own words, here is Weston Jenkins and his ‘Aviation Magnus Opus‘.

One Old Boy’s Airplane Story

Weston H. Jenkins – May 2014

It was a Sunday in May of 1927. I know it was a Sunday because our family was on a picnic. My parents had brought along a newspaper. My mother showed me the headlines (at three I didn’t yet read) and said that a man named Lindbergh  had just flown across an ocean. She said very firmly that this was a big day and that I should remember it.

had just flown across an ocean. She said very firmly that this was a big day and that I should remember it.

I do. Thus began my awareness of things aviation. This developed into an interest in aircraft, large and small, which has persisted to this day (I just turned 90).

Such interest was not unusual at the time, because that was more or less the beginning of what is called ‘The Golden Age of Aviation‘. Headlines were often appearing: records were being set. The Navy dirigible Los Angles flew over our neighborhood in 1929. Everyone was out. Unforgettable.

By seven, I was devising representations of airplanes with parts from my Erector set. There was no hesitation to bend them as necessary. Enthusiasm.

Christmas brought a construction set dedicated entirely to airplanes assembled from an assortment of metal parts with screws and nuts. A year after that came a similar set for building blimps and dirigibles. The big boys were building and flying little balsa models around the neighborhood. Fascination.

Given a few sheets of balsa, I essayed making simple gliders. Failure at 9.

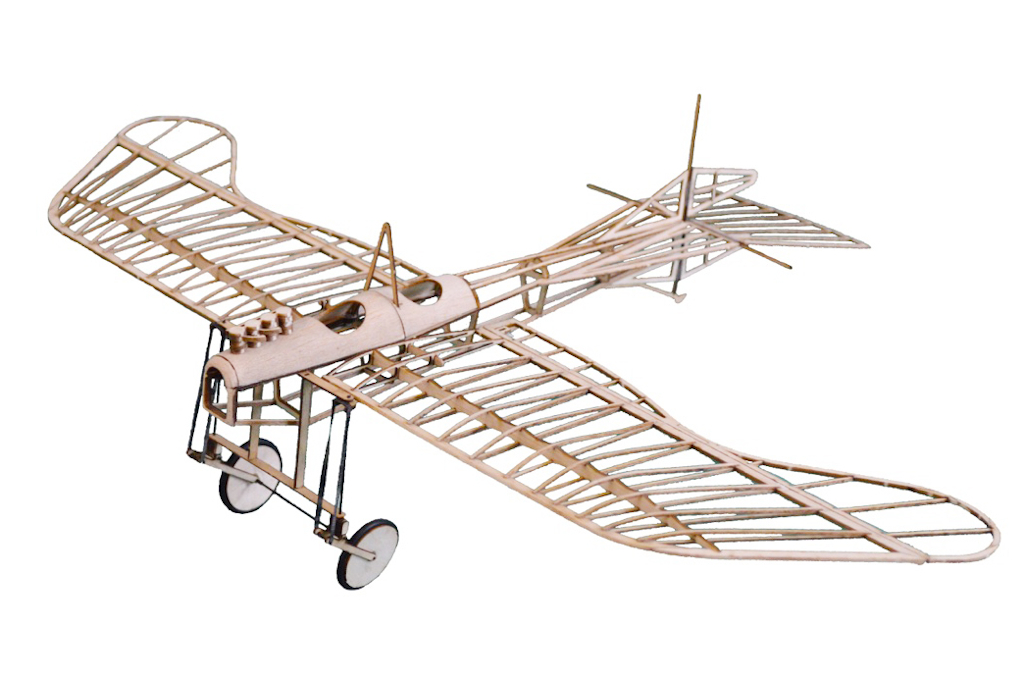

At 10, my 12-year-old cousin showed me how to build flying models and took me to a hobby shop where I bought a 24-inch DeHavilland Puss Moth kit for 25 cents.  I built the fuselage on the floor of my aunt’s front porch. Proud of my accomplishment, I wanted to take it to show my cousin the accomplishment, so my mother (a firm person, remember) put the structure in a paper bag and, as was her habit, closed the bag by firmly twisting its top. Total collapse. Tears.

I built the fuselage on the floor of my aunt’s front porch. Proud of my accomplishment, I wanted to take it to show my cousin the accomplishment, so my mother (a firm person, remember) put the structure in a paper bag and, as was her habit, closed the bag by firmly twisting its top. Total collapse. Tears.

With more glue and patience the airplane was completed a week or so later. To me it looked good, looked airworthy. Lacking any knowledge of balance or trimming, I wound it up and launched it. It simply dove into the ground and destroyed itself. Failure again.

But the urge was strong and the pattern was set. Quitting was unthinkable. Whenever a dime for a kit (usually Guillow’s) and a nickel for glue came to hand there was another project, invariably ending up warped like a potato chip because the only method of spraying water for shrinking the tissue was to hold my finger over the bathtub faucet. What was intended as a moistening was always a thorough soaking. Discouragement.

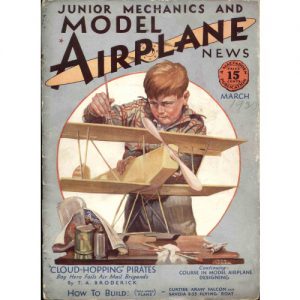

Reading helped a lot; that and the companionship of a few friends I was proselytizing. First came Model Airplane News. Edited by an M.I.T. graduate named Charles Hampson Grant, it was something of a challenge. Unlike the hobby magazines of today, which have morphed into mainly product reviews and colorful advertising, M.A.N. contained solid stuff, information on new full-scale aircraft, model airplane flight theory, plans from which one could actually build, all in serious black-and-white except for the cover painting. Along with this were Bill Barnes Air Trails and Flying Aces, both partly exciting (to a youngster) aviation fiction and partly model material, always with workable plans or dimensioned drawings from which workable plans could be laid out. Even Popular Aviation, the mechanics magazines and the Sunday papers (think the syndicated Junior Birdmen) sometimes had model airplane articles with directly usable plans. Encouragement.

Edited by an M.I.T. graduate named Charles Hampson Grant, it was something of a challenge. Unlike the hobby magazines of today, which have morphed into mainly product reviews and colorful advertising, M.A.N. contained solid stuff, information on new full-scale aircraft, model airplane flight theory, plans from which one could actually build, all in serious black-and-white except for the cover painting. Along with this were Bill Barnes Air Trails and Flying Aces, both partly exciting (to a youngster) aviation fiction and partly model material, always with workable plans or dimensioned drawings from which workable plans could be laid out. Even Popular Aviation, the mechanics magazines and the Sunday papers (think the syndicated Junior Birdmen) sometimes had model airplane articles with directly usable plans. Encouragement.

Then came some flying success. A small plane of light construction with a single-surface built-up wing called Zephyr was presented in Air Trails. It was very satisfying. More so was the Flying Aces Moth which appeared in the Flying Aces issue of August 1937. Designed and drawn by Herb Spatz, it had only a 24” wingspan, but powered up by a winder built from an eggbeater, it flew so well that I saved the plans and built another, equally satisfactory, about 15 years ago. On a roll.

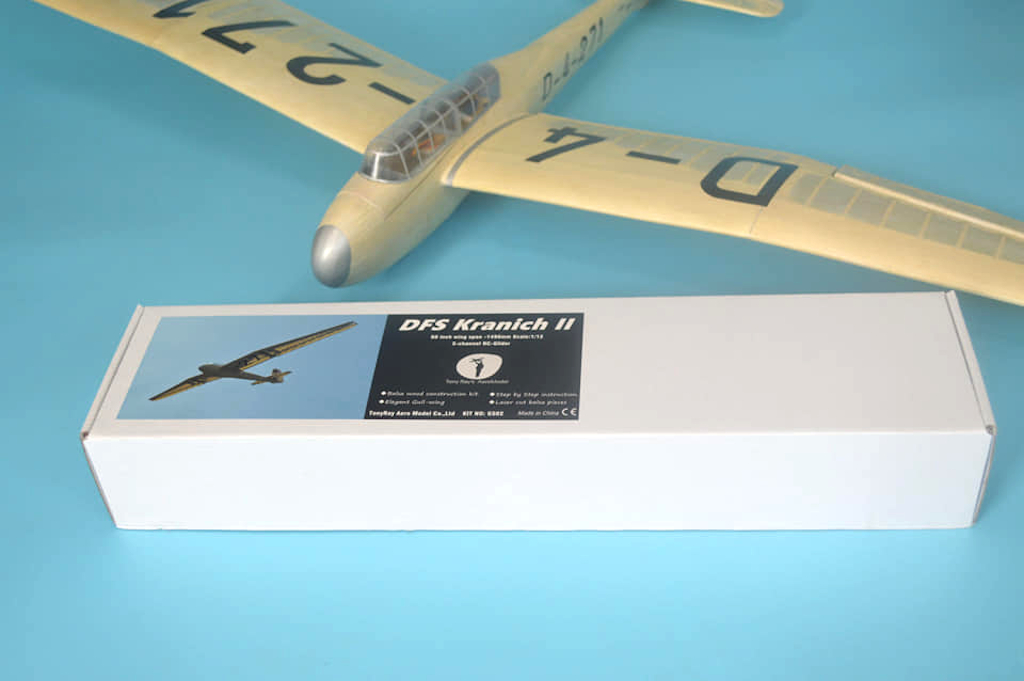

Larger planes, suitable for free-flight contests, followed. These were “Stick” models, ‘Fuselage” models and a few gliders, e.g. the Berkeley Sinbad, circa 1948. Somewhat unattractive in the side view, Dick Korda’s Wakefield, built from a Megow’s kit, flew so well that chasing wore me out. That must have been in about 1940.

Interest in wound rubber and powerless flight has persisted to this day, but is mostly satisfied by reading.

Gas power was coming along. Plans for the big Brown Jr. powered Kovel-Grant KG airplane set me to thinking. They were spread over two or three installments of Model Airplane News, probably in about 1935. The engine cost $21.95, but it was just to dream about. I was in sixth grade and $21.95 was close to my father’s weekly earnings.

There was some dim hope, however. A company called G.H.Q. introduced a kit of finished engine parts, including tank, spark plug, spark coil and condenser for five dollars. By saving school report card reward money supplied by my grandfather, I went for it. Horrid mistake.

The engine was not difficult to assemble, except that the fuel line had to be soldered to the needle valve. Good soldering was beyond me, but eventually it all came together and was ready to run. The fuel was unleaded gasoline mixed three to one with No. 70 motor oil. Number seventy…try to find that these days. That sucker never did fire. At that time Packard had introduced somewhat miniaturized spark plugs in their cars. I forced one into the spark plug hold. No luck. Hours of prop-flipping yielded nothing but an aching arm and badly swollen fingers. (I have a friend who relates that, in desperation, he finally succeeded in making a G.H.Q. function by employing an automobile spark coil and a 6-volt battery. I think to this day that the thing must have run on the spark energy alone.) It’s likely that the problems encountered with this engine set the entire hobby back as least a year. Frustration.

By the freshman year at high school my report cards had bought me a new Brown D engine (ten dollars) and a 6-foot Thunderbird airplane kit from the Bay Ridge Model Airplane Company for less than five dollars, including glue and dope. Kits never had enough of either, but I had come to expect that.

Now the problem of work space arose. At first it had been my aunt’s porch floor. Then at home it had been the top of an upended orange crate. This progressed to a desk in my bedroom with newspapers always spread on the floor to catch trash and glue and paint droppings. The Thunderbird was big, though, so it was back to the floor, this time working on a board which could be pushed under the bed. I built the entire airplane on my knees. Try THAT now! Determination.

Expectations were high. The Thunderbird looked flyable and the engine ran. It seemed too big to hand launch and takeoff from the ground seemed logical. It wasn’t, quite. There was a ground loop, the tail tore off, and that was that. Later a friend took it over, fixed it, and got it to fly successfully. Setback.

There followed a series of gas-powered models from kits and from magazine plans. Among them was a handsome Comet Clipper  which had a nasty habit of taking off, starting a promising flight, then entering a flat death spiral, around and around and finally a cartwheel. There must be something better than helplessly watching a thing like that. Radio control? Fat chance!

which had a nasty habit of taking off, starting a promising flight, then entering a flat death spiral, around and around and finally a cartwheel. There must be something better than helplessly watching a thing like that. Radio control? Fat chance!

It was 1939 and the National Soaring Meet was being held, as usual, at Harris Hill, near my hometown, Elmira, NY. A friend of mine and I were camping and working as volunteers on glider crews. A young man named, I believe, Clinton DeSoto, appeared with a truly huge radio-controlled glider which he planned to tow with an automobile. It had full-size glass radio tubes and a rudder which would go to straight or to a single direction. I never did see it fly, but the fire was ignited. You needed an amateur radio license to operate a thing like that. Wait a while.

<<End Part 1>>